On 10 September 2018, the Austrian Fund for Science (FWF) hosted a symposium on Social Ecology at the BEOPEN science festival in front of the Museum for Natural History in Vienna. At the event, Marina Fischer-Kowalski was presented with the ISIE Society Prize, a prestigious award with which the International Society for Industrial Ecology recognized outstanding contributions by senior scientists in the field. The event was opened by Ellen Zechner, the vice-president of FWF, and Hubert Hasenauer, the rector of the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences. In the main lecture, Marina Fischer-Kowalski showcased her work focusing on the sociometabolic analysis of hunter-gatherers in the Nicobar Islands (India) and the transformation of their lives through the aid received after the 2004 Tsunami, and her work for the preservation of and creation of a UNESCO biosphere reserve on Samothraki, a Greek island. The president of the Wuppertal Institute, Uwe Schneidewind, discussed the role of citizen-scientists and the need for scientists to enter the public debate. Helga Weisz, a professor at Humbolt University, discussed industrialization and the role of fossil fuels in the advances of democracy and asked how a shift to renewable resources will affect social organization.

In his address, ISIE president Edgar Hertwich lauded Fischer-Kowalski’s contribution to the conceptual development of the field, the positioning within sustainability science, the initiation of a powerful dataset that is now a core element of the United Nations’ Material Flow database, and her role in the institutional foundation of the field.

Read here Hertwich’s laudation (machine-translated from German to English).

Dear Marina, dear audience,

How do we humans destroy nature?

We humans arose out of nature, were part of nature, we are still dependent on it in multiple ways, as the heat waves, draughts and failed harvests of this year illustrate.

Marina Fischer-Kowalski has dedicated her life to answering this question - that's what I'm just assuming, without you writing that down. You've made great strides to answer this question and shaped the language we use for this purpose today.

I will try to illustrate this.

One can ask this question once in subquestions:

- Why?

- How much?

- Why do we have such a hard time to stop?

- How can we manage to save nature and humanity?

Why?

Let's start with Rene Descartes and the Enlightenment, more precisely the duality of body and mind. Their correspondence at the macro level is the duality of nature and culture. The point is that we humans inhabit both worlds, body and mind, and the mind, as far as we know, needs the body, which in turn depends on nature. In order to take care of their bodies, humans have subjugated nature, a process that you call the colonization of nature. We use the achievements of culture to extract from nature what is necessary to sustain and provide comfort to the body.

It has long been a paradox to me why the conventional conception of sustainability research, as described by the US Academy of Sciences, turned the duality into a dichotomy. Sustainability research as either social science or natural science. Natural science sought to understand natural processes in order to describe all the ways in which humans damage nature, however, without describing what happens to the resources once extracted and before becoming waste. The humanities and social sciences dealt with the “human dimension” of global environmental change, which was strangely devoid of materials. They dealt with the symbolic importance of nature in culture and with the design of the markets for resources and emission rights, ignored, at least as an object of research, the material dimension of human society which is also constrained by the laws of nature.

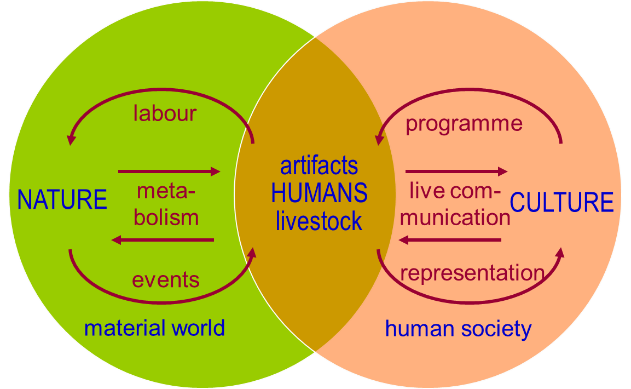

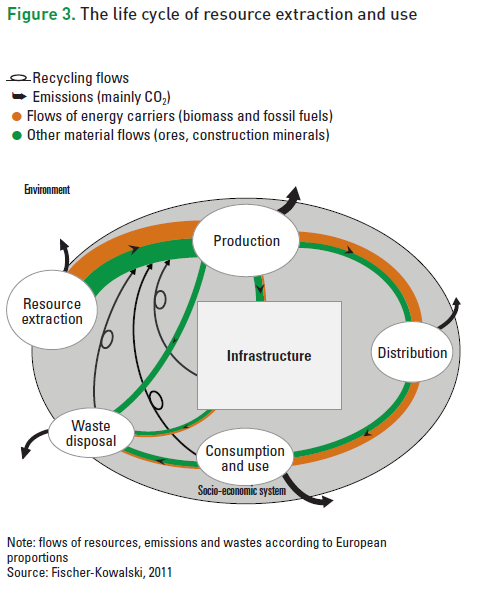

You have propagated a paradigm shift so that sustainability research would address the material nature of our human society. The Venn diagram described by you as the potato graph represents the overlap that needs to be understood: how does culture reproduce itself through the use of natural resources and the production of pollutants? You have situated your work at the core, in the area of overlap between nature and culture, which is comprised of us humans, our artefacts and our domesticated animals and plants. A sophisticated conception has been developed, in which the exchange of materials between nature and the material dimension of society, the anthroposphere, is described as the social metabolism. The metabolism also describes the flow of materials and energy within the anthroposphere, through extraction, production, distribution, and consumption to waste treatment. Society has, if you want to, it’s anabolism and catabolism.

How much nature does humanity use?

Your research approach was clear: to understand the corporeality of culture, you have to measure it, in kilograms and megajoules. The quantification of this social metabolism cannot be avoided. The idea of studying the material turnover of humanity had already been suggested many great minds before you, as you have shown in your meticulous historical literature study. You and your team were instrumental in developing a system according to which these observations were standardized, made comparable, and performed by statistical agencies. The material accounting system according to EUROSTAT presented here was crucially influenced by you and your team. I am also looking at Helga Weisz, in the audience. Within the International Resource Panel, you have helped to make this work the global standard. Today, the dataset of material flows of most nations that you initiated is at the heart of the United Nations material flow database, which is used to advise governments. Two weeks ago, I was in Argentina to present work of the International Resource Panel, led by Heinz Schandl – another graduate of the group, to the G20. It built on this database. These achievements show that you not only have good ideas, you also have the persistence and the gift of persuasion to help these ideas break through.

It is clear that this rapid increase in social metabolism has significant negative consequences, not least for the climate and the pollution of the oceans. Why do we not stop then?

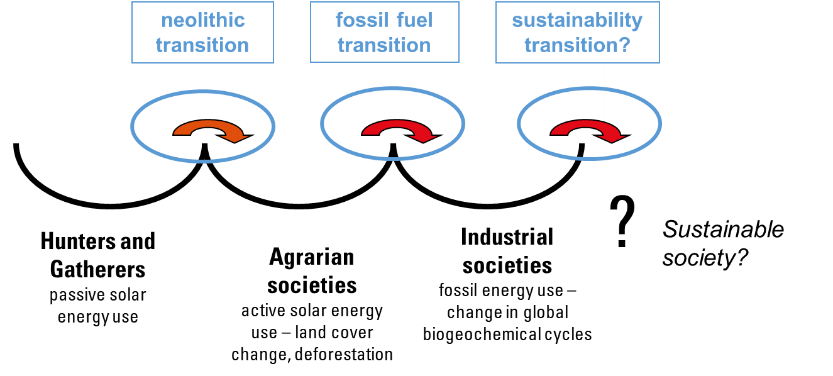

To understand this, you have introduced the concepts of sociometabolic regimes. Regimes indicate possible, stable forms of human existence: hunter-gathering, agrarian society. Each regime is characterized by a characteristic metabolism, a population density, a social organization and its stabilizing culture. The pattern of the social metabolism is part of the cultural program of those societies. There is a stable mutual interaction between both, which makes it harder to initiate a socio-ecologic transition from one regime to another.

Can we still save our human society?

A socio-ecological transition from one regime to the next is difficult and rare. You have taken a historical approach to study regime change, including revolutions which happened during the transition from the agrarian to the industrial societies. Now we live in a regime that is in no way stable and sustainable. If we do not make the turnaround, things look bad for us.

These are big questions. You have given us concepts that we can use to put these questions into words. You have been tireless in helping us to pursue the questions not only conceptually but also quantitatively. Many more questions arise that need answering to get out of the mess as we are in society.

One of the most important questions is: how can culture induce society to limit and control its metabolism, not to maximize it?

You have defended this approach against those corrupting forces that would like to find a win-win as a way to preserve and dress up the status quo.

Dear Marina, you were nominated by Tom Graedel, the founder and first president for the Society Prize. The Prize Committee of the International Society for Industrial Ecology has unanimously decided to award this prize, the Society's highest honor, to you.

As President of the Society, I would also like to underline your contribution to the institutionalization of our new research direction. You were president 10 years ago and did an important job for the society. The Institute of Social Ecology, founded by you, which today is based at the University of Natural Resources, has become an incredibly successful research institute. You have understood the social and human nature of research. What a success!

So it gives me great pleasure to present you the Society Prize of the ISIE.