This blog post is part of a series on the 2017 Graedel Prize Winners.

Read the other blog post here: Choice of Allocations and Constructs for Attributional or Consequential Life Cycle Assessment and Input‐Output Analysis..

Questioning conventional thinking is never easy. In the case of the circular economy (CE), however, it is critically important. Over the past eight years, governments worldwide have invested billions in developing CE initiatives and activities—but over that same time, my co-authors and I have discovered that there is significant potential for the CE to fail to deliver on its environmental promise.

Our research started with a deep exploration of how exactly recycling generates environmental benefits. We found that the sole way recycling reduces environmental impact is by reducing production of higher-impact materials, in particular primary materials. As a next step, we formalized the economic market mechanism by which recycling can displace production. Alarmingly, we discovered that such displacement is not guaranteed (even worse, new research by Remi Trudel and colleagues has shown that the mere option of recycling actually increases people’s material consumption). Over successive projects, we developed methods for estimating how much production is displaced by recycling, demonstrated that methodology for specific materials, and proved that recycling doesn’t divert existing material from landfill.

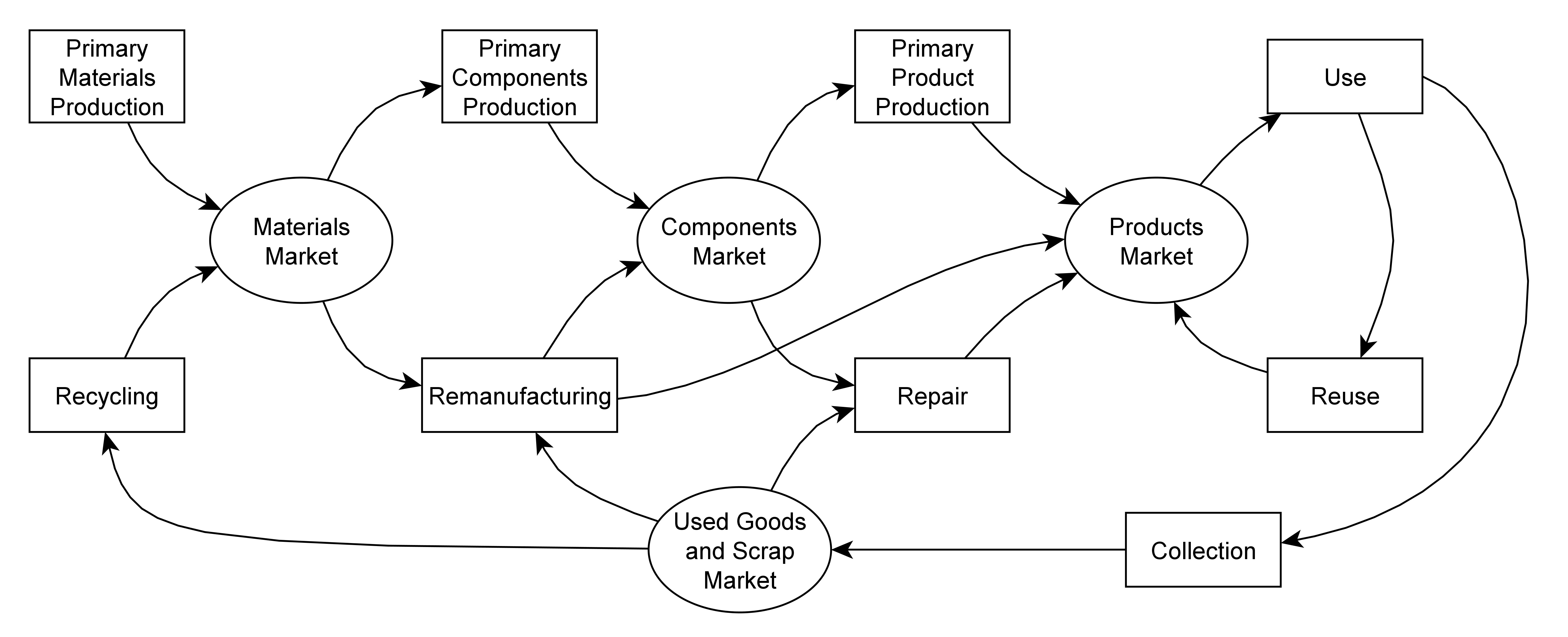

However, we quickly realized that the effects we were uncovering encompassed more than just recycling. As the CE gained traction, we started to notice other CE activities that seemed like they had low potential for displacing primary production. As was the case with recycling, both popular sentiment and academic literature seemed to be ignoring key elements of the circular economy. Perhaps nothing demonstrates this more clearly than the “circular economy diagram” from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, in which economic mechanisms (such as markets) are conspicuously absent (in contrast to our version in Figure 1).

Figure 1: The circular economy diagram depicted more realistically, with markets mediating each step

We knew from our recycling experience that we faced an uphill battle against CE mantra, but we recognized the importance of generalizing our findings about recycling to all CE activities and communicating them to a larger audience. The challenge was how to cleanly and understandably convey both the potential benefit of CE activities and the potential for increased production to eat into that benefit or erase it altogether.

As we formalized the mechanism by which the CE can go wrong, we realized there was a clear analogy to energy efficiency rebound. The compelling parallel was that where energy rebound is about lower use cost leading to more use, CE rebound is about lower material/product prices leading to more production.

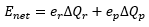

When we arrived at the equation that appears in the article, we felt we had a succinct way of showing the total environmental effect of CE activities: CE activities can have different (often lower) per-unit impacts than equivalent primary activities, but can also affect the number of units produced. Thus the net effect of increased CE activities ![]() is a function not only of the per-unit production impacts of primary

is a function not only of the per-unit production impacts of primary ![]() and secondary

and secondary ![]() products, but also of changes in the quantity of primary

products, but also of changes in the quantity of primary ![]() and secondary production

and secondary production ![]() :

:

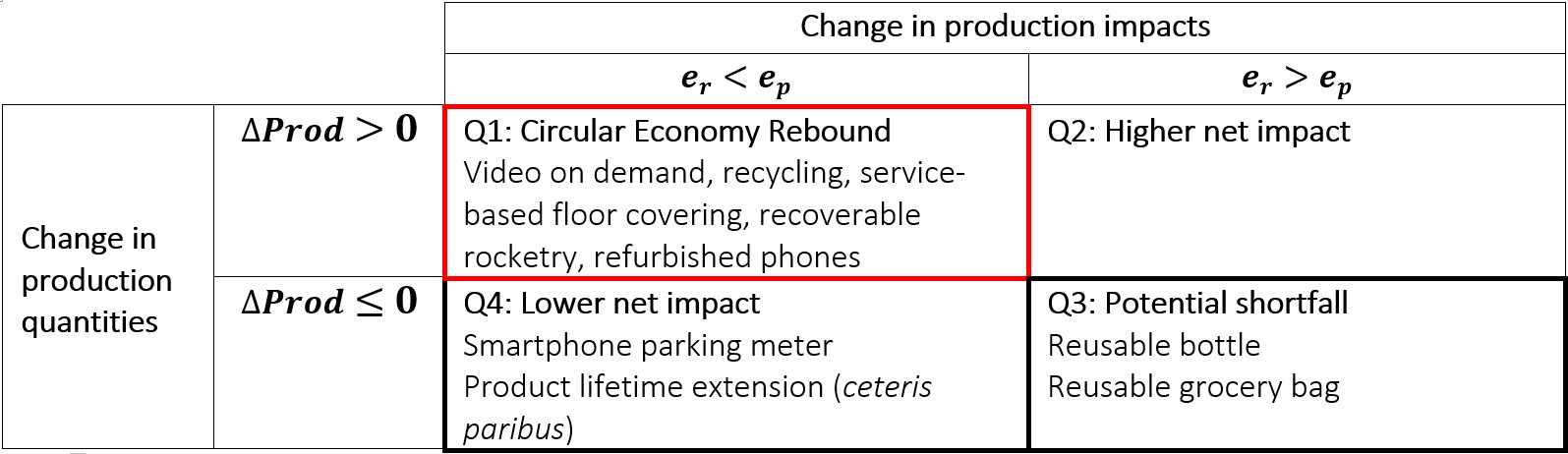

When CE activities increase total production ![]() ), it is similar to when improved efficiency causes increased use, so we named this effect circular economy rebound. The equations also gave us necessary conditions for CE activities to reduce net impact: not only must primary production decrease, but the increase in secondary production must be proportionally lower than the difference in per-unit impacts

), it is similar to when improved efficiency causes increased use, so we named this effect circular economy rebound. The equations also gave us necessary conditions for CE activities to reduce net impact: not only must primary production decrease, but the increase in secondary production must be proportionally lower than the difference in per-unit impacts ![]() .

.

Almost incidentally, our equation also enabled us to formalize the dangers of another aspect of the CE, reusable durable goods. In this case, refers to the per-unit impact of the reusable good compared to those of some single-use good, . Reusable durable goods often have higher per-unit impacts than single-use alternatives ![]() , but promise to lower the number of units produced. Here, too, so long as

, but promise to lower the number of units produced. Here, too, so long as ![]()

reusing durable goods reduced net impacts. But if not (for instance if the reusable good is not used a sufficient number of times to displace enough single-use goods), net impacts increase—an effect we named shortfall. This effect is going to be increasingly important to pay attention to as more governments move to ban single-use plastics. Alternatives to single-use plastics such as paper, cloth, and biopolymers almost invariably have higher per-unit production impacts, so the only way they can reduce net impacts is by sufficiently lowering the number of units produced and used. It is too soon to know whether this is happening with bans already in place.

Looking at the changes in per-unit production impacts and changes in production together gave us a succinct way of conceptualizing the four effects CE activities can have (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The four possible effects of circular economy activities. The goal is to encourage activities in Q4, while limiting rebound in Q1 and guarding against shortfall in Q3.

The concept of circular economy rebound should change the way we look at and judge the merits of the CE. CE rhetoric universally heralds it as a way to both reduce environmental impacts and grow the economy. If this is true, it appears that rebound is baked in as a central feature of the CE. For instance, the European Regional Development Fund claims that the €30M it is investing in the Scottish CE will add €100M in new economic activity. As we mention in the article, the consulting firm McKinsey and Company advises its clients to find CE investments that do not cannibalize existing production, thereby guaranteeing rebound.

Yet, one simple equation demonstrates that if environmental protection is a true goal of the CE, then growing consumptive markets cannot be viewed as a feature of the CE, but a serious problem. At best, increased production absorbs some of the benefit of CE activities—at worst, it outpaces the per-unit impact reductions and increases overall environmental impacts.

There is clearly promise to the idea of cycling industrial ‘nutrients’ in a circular economy. However, we must develop the CE with (as Julian Allwood would say) both eyes open. The potential for failure is real and, so far, almost completely unexplored. Our hope in writing our article was both to point out the potential dangers of the CE and to call scholars and practitioners to engage in critical research to help us understand and prevent them. Unfortunately, since our article was published we have seen more focus on the same misguided targets—for instance, none of the European Commission’s 2018 ‘circularity’ metrics have to do with displaced production, and efforts to measure the effect of plastic bag bans have emphasized reduced litter but haven’t assessed shortfall from increased production of alternatives. On the other hand, we have seen scholars adopt the terminology and economic thinking we propose, suggesting momentum may be building.

One thing that should be clear is that merely unleashing—or worse, subsidizing—the CE in a free market will undoubtedly create rebound. There is hope for the CE to achieve its promise, but only if we are intentional about ensuring that CE activities displace rather than merely add to our current economic activity.