Shahana Althaf and Callie Babbitt

Today we live in a technology-dependent world, where new electronics are constantly flooding the market and consumers are tempted to upgrade their working gadgets with newer and shinier models. As a result, news articles and academic studies have warned of a looming “tsunami” of electronic waste. Past research in Industrial Ecology has shown that product lifespans are shrinking, that many electronics contain hazardous materials like lead and mercury, and that these devices are sometimes managed improperly once discarded by consumers, leading to social, economic, and environmental impacts.

But at the same time, Industrial Ecology studies have also shown that products and their impacts are fundamentally changing. For example, a smartphone now provides all of the functionality that once took a separate digital camera, MP3 player, portable navigation device, and e-reader. Watching TV once required a heavy cathode ray tube (CRT) television that contained hazards like lead, but now uses a slim flat panel TV that contains scarce metals like indium. The fundamental question is whether these underlying changes in technology and consumer behavior are leading towards sustainability improvements or creating new challenges.

This question is difficult to answer because the needed data are hard to find, especially for analyzing nascent trends. In the U.S., where we are located, the available estimates of national e-waste flows dated back to 2010, with little recent information about product consumption, material profiles, ownership, or waste generation. Therefore, we aimed to contribute an up-to-date picture of electronic product consumption, e-waste flows, and attendant material, design, recycling, and policy challenges.

This material flow analysis was made possible by high quality industry data on electronic product sales and shipments covering the past 50 years. Product lifespans distributions were creating using consumer surveys about product ownership and discard behaviors. To estimate the material profile of the products, we disassembled nearly 100 products ranging from old VCRs to the latest smartphones. We recorded, compiled, and published the product bill of material data to be available to the industrial ecology community for future studies on consumer electronics.

Disassembled smartphone; photo by Callie Babbitt

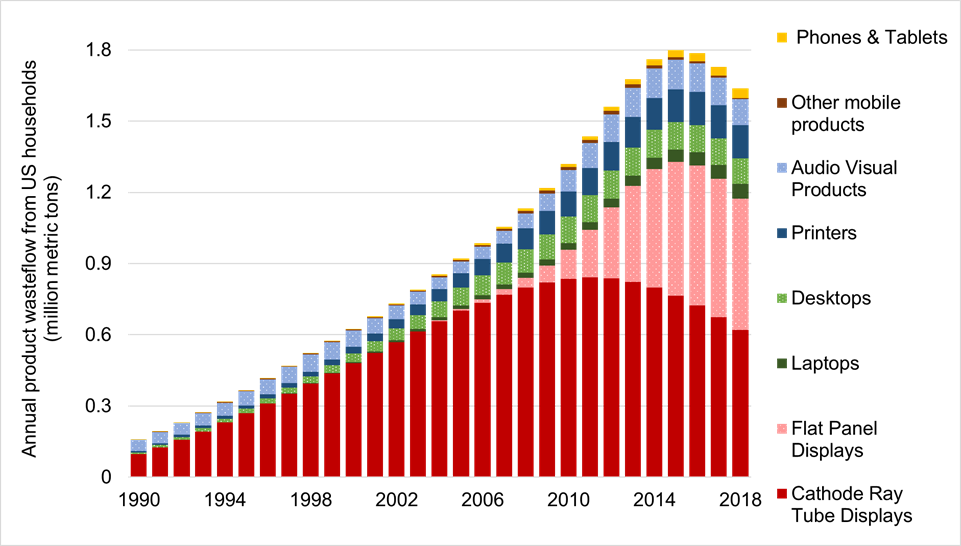

The surprising result from this analysis was that the mass of e-waste in the U.S. is currently in decline. Most of the observed decrease is due to consumers phasing out large, bulky products like cathode ray tube TVs and instead buying light-weight flat panel displays. Moreover, consumption in recent years has been dominated by small mobiles devices which contribute only a small fraction to the total mass of the waste stream. In parallel, many products now use lighter materials, like aluminum and magnesium, instead of plastic or steel found in designs a decade ago.

Declining trend observed in annual waste flow (in million metric tons) of commonly owned products in U.S. households. The scope includes the 20 most common product categories making up the electronic product ecosystem in an average U.S. household. Graph taken from the published study.

But the study also showed that while electronic waste is no longer the ‘fastest growing waste stream’ in the U.S., its recovery for reuse and recycling is more important than ever. The e-waste stream is increasingly enriched in critical metals like cobalt and indium and contains precious metals at a concentration that is higher than observed in many natural ores. Yet many of these materials are not easily recoverable with current technology. In addition, the dematerialization that reduced weight was often enabled by product design features that would make recycling more difficult, including parts permanently attached by adhesives, miniaturized components and fasteners, and minimal design for disassembly and repair.

While these results came from an academic study, the trends are similar to real-world observations. The U.S. lacks federal e-waste regulations, but 25 states and the District of Columbia in the U.S have some form of e-waste law, typically following an extended producer responsibility (EPR) model. Several state programs have started to see a similar decline in mass, with California and Oregon reporting a 10% decline from 2018 to 2019 and Vermont dropping 6% in collection. These trends are particularly challenging in states that specify mass-based targets for electronics collections and recycling.

Policies are also limited by what products they regulate. This study focused on the most commonly owned consumer electronics owned by U.S. household, which mirrors the list of products frequently covered by state laws. However, many emerging electronics are not included – things like smart home devices, solar panels, automotive electronics, and appliances are all on the rise, but rarely included in U.S. e-waste laws. There is a critical need for policy mechanisms that are forward-looking and able to evolve with the anticipated future trends in electronics innovations. We hope that other industrial ecology researchers will use and expand the model we shared to study waste flows associated with new products and materials and understand the outcomes of technological progress and consumer behavior change.

While the results of this study surprised us, the broader implications only underscored our view that sustainable solutions for electronics require a proactive approach, informed by good data, and engaged in by all stakeholders. Designers, manufacturers, recyclers, consumers, and policy makers all have a critical role in creating electronic products that provide sustainability benefits without paying a steep environmental cost. Despite the immense body of Industrial Ecology research that exists on electronics and e-waste, there are still pressing challenges that motivate future study on the solutions needed to transform electronic “waste” into a valuable resource within the circular economy.